Malware like Zeus and its variants inject themselves into a user’s browser to steal banking information. This is a man-in-the-browser attack. So-called, because the attacker is injecting malware into the target’s browser.

Man-in-the-browser malware uses two approaches to steal banking information. They either capture form data as it’s sent to a server. For example, malware might hook PR_Write in Firefox to intercept HTTP POST data sent by Firefox. Or, they inject JavaScript onto certain webpages to make the user think the site is requesting information that the attacker needs.

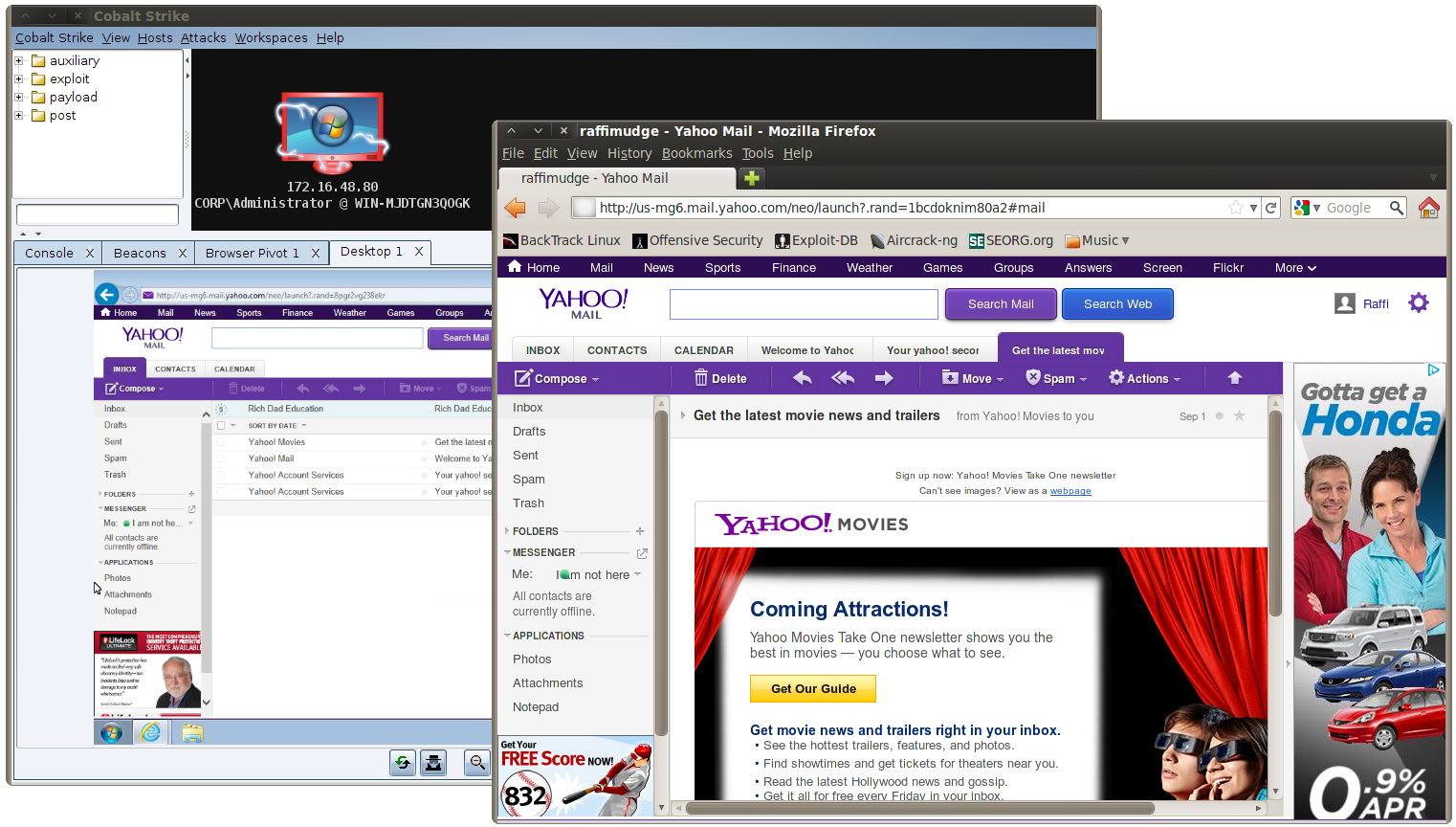

Cobalt Strike offers a third approach for man-in-the-browser attacks. It lets the attacker hijack authenticated web sessions–all of them. Once a user logs onto a site, an attacker may ask the user’s browser to make requests on their behalf. Since the user’s browser is making the request, it will automatically re-authenticate to any site the user is already logged onto. I call this a browser pivot–because the attacker is pivoting their browser through the compromised user’s browser.

Cobalt Strike’s implementation of browser pivoting for Internet Explorer injects an HTTP proxy server into the compromised user’s browser. Do not confuse this with changing the user’s proxy settings. This proxy server does not affect how the user gets to a site. Rather, this proxy server is available to the attacker. All requests that come through it are fulfilled by the user’s browser.

For a penetration tester, this approach to a man-in-the-browser attack is interesting. Here’s why:

- It’s site agnostic. You don’t have to customize the attack for each site you want to target. This is good, because penetration tests are time constrained.

- The browser pivot is a very visual demonstration. You open your browser and go to a sensitive site. Voila, you’re there as the user. This is a very powerful way to demonstrate risk to an executive and convey what an advanced threat actor could do once they compromise a system.

- It’s hard to detect. All of the attacker’s activity is mixed in with the user’s legitimate activity. All requests come from the same browser. How do you sort this out? If you’re a penetration tester replicating an advanced actor, you want capability in your kit that challenges your customers.

If your work involves stealing data to demonstrate risk and highlight a viable attack path, the utility of browser pivoting is apparent. This tool is a quick and seamless way to steal browser sessions. If the session is secured with a cookie, think of this tool as a convienence. If the session is secured by a client SSL certificate, whose private key is stored on a smartcard, then browser pivoting may be your only opportunity to steal that session. [Yes, this works.]

If you’d like to see Browser Pivoting in action, take a look at this new video. It demonstrates how to browser pivot into a webmail account, a local Wiki secured with HTTP server authentication, and a local Wiki secured with a client SSL certificated stored in a password protected keystore.